Guatemalan photographer David Rojas captured some gorgeous footage in his homeland; a bathing resplendent quetzal. These jewel-toned birds with their stunning plumage and streaming tail-feathers are the largest members of the family Trogon and are found in high-elevation tropical forests of southern Mexico and Central America. The sizable, showy birds have long captured the imagination of the indigenous Mesoamerican people of the region and are designated the national animal of Guatemala.

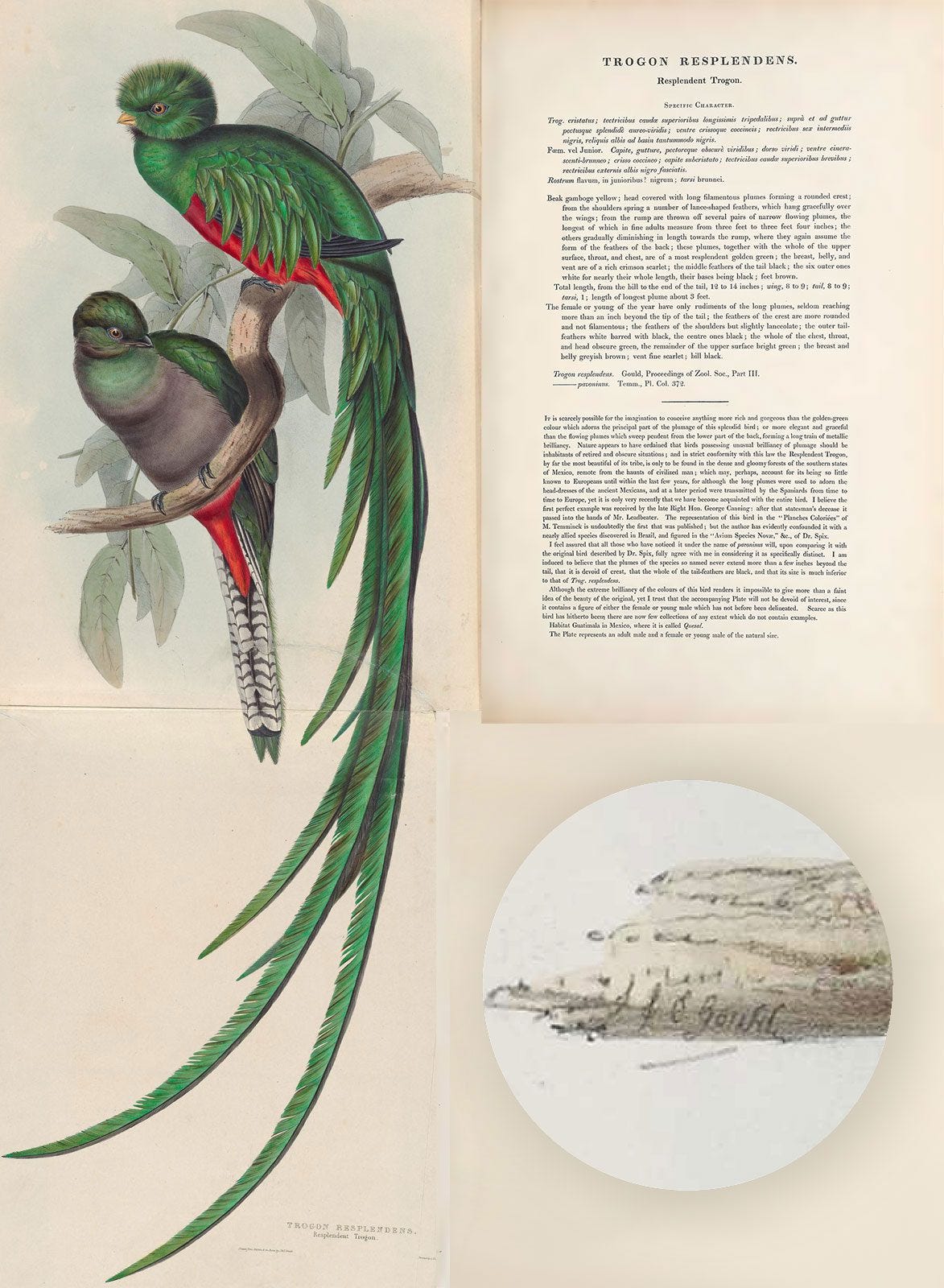

Resplendent quetzals grow to roughly 36-40 cm (14-15.7 in) long. Their tail feathers, only found on males and particularly developed during breeding, add another 65 cm (25.5 in) to the bird’s overall length. Even still, given their bright coloration and large size, they stay well-camouflaged in the forest canopy and subcanopy where they spend most of their time. This hiding ability is thanks to their highly iridescent feathers, an adaptation that allows them blend into wet, shiny foliage. Their clear, dark eyes are evolved to search out food and avoid predators in their shaded, leafy environments. These forest denizens are “cavity nesters,” using their stout bills to excavate burrows out of decomposing tree trunks or colonizing and enlarging holes made by woodpeckers or insects.

While resplendent quetzals are primarily fruit-eaters, they will snack on insects, snails, amphibians and small reptiles. Older birds tend to consume a larger percentage of fruit in their diet than the younger ones do and parents will often collect insects specifically to feed to their chicks during rearing. But one thing resplendent quetzals of any age really love is avocados: they will swallow the fruit whole, consume the flesh and then regurgitate the pit. In fact, these birds play an important role in helping disperse seeds throughout the forest, helping disseminate the seeds of at least 32 tree species.

Resplendent quetzals live alone when not breeding, migrating to lower elevations for some months for feeding. However, they are monogamous breeders and will carve out a territory during the rearing of their chicks. Solitary and largely silent (to avoid attracting the attention of predators) through much of the year, resplendent quetzals do put on a display of song and dance during mating season, the pair engaging in a call and response session. The male’s elongated tail feathers play an important part in the bird’s mating display—he will fly high above the tree canopy and plunge back down towards the female, his long train of feathers rippling behind him. If she’s agreeable, she’ll join him in a synchronized dance. A mated pair will choose a nesting site and the female will lay a clutch of one to three eggs (usually two) on the unlined nest floor of their tree hollow home. The pair will take turns incubating the eggs, with the male folding his long feathers over his back to fit into the nesting compartment as necessary; sometimes he’ll leave a length of feather sticking outside of the hole, resembling a fern growing on a tree. Towards the end of the month-long rearing period, females will oftentimes leave the chicks with the male partner for him to finish the feeding and rearing process. Young quetzals can fly about a month after hatching, although it may take up to three years for males to develop those distinctive tail feathers.

It is those long, magnificent tail feathers that have long been treasured in Aztec and Mayan cultures. The resplendent quetzal is associated with the snake god Quetzalcoatl, the important deity credited with creating humanity and—in his role as benefactor—gifting humans with maize. Quetzalcoatl is depicted as a feathered serpent, his neck adorned with the feathers of the resplendent quetzal. Priests and nobility in both of these Mesoamerican cultures would wear headdresses of the streaming tail plumes, and the Aztecs required bundles of quetzal feathers in their tributes. However, because the bird was sacred, it was illegal to kill a resplendent quetzal; so the feathers were collected by trapping the birds, plucking the prized plumes and then releasing the birds back into the wild. The feathers were so valued in these cultures that they were used as a medium of exchange, a tradition that is echoed in the present day, with Guatemalan currency being called the “quetzal.”

Reflecting the difficulty and high mortality rate of resplendent quetzals kept in captivity1, the bird was and is considered a symbol of freedom and liberty. The country’s state flag is even adorned with this symbol of liberty, a resplendent quetzal perched atop a scroll which indicates the date of Central America’s independence from Spain.

Source for today’s video is from Rojas’ Instagram page, linked here.

Click through to the links below for more information on this beautiful bird and its cultural significance.

American Bird Conservancy: Resplendent Quetzal, “Sacred Species”

WhiteHawk: National Bird of Guatemala: The Resplendent Quetzal by Jenn Sinasac, 9/25/23

DataZone by BirdLife: “The Resplendent Quetzal in Aztec and Mayan culture” 9/8/08

Wikipedia: Resplendent quetzal

David Rojas, Photographer (Facebook page, in Spanish)

Scientific study has since found that resplendent quetzals in captivity perish due to consumption of water containing iron. If they are fed tannic acid and iron is avoided, they can be successfully kept and bred, as is being done at Miguel Alvarez del Toro Zoo in Tuxtla Gutierrez, Chipas (Mexico).

Beautiful birds. Thank you for this gift with my second coffee this morning.

While I feel a bit cloddish bypassing those glorious birds, don't you just love those old 19th century typefaces? There is something very satisfying about a book that has survived more than a hundred years, even if they are often full of typos and uneven inking. The smell and the feel of them is something no contemporary publication can hope to rival, much less emulate.