Sometimes a Cigar Is Just a Way to Annoy a Fairy

"Princess Nicotine" showcased the height of 1909 cinematic special effects

Today’s gif is a segment from a 1909 cinematic short, “Princess Nicotine” (a.k.a. “The Smoke Fairy”). It was celebrated as one of the best special-effects film of its day, even earning an article that same year in Scientific American highlighting the techniques used to put the little smoking fairy on the same frame as a full-sized man, astounding audiences of the time. I imagine that in a time of less regulation on tobacco, audiences of the era were probably less surprised to see a child smoking a cigarette than modern audiences would be. Perhaps though some viewers might have been familiar with a certain Sigmund Freud and his recently-published work on symbolism in psychoanalysis that they might have chuckled (or alternately, been completely horrified) at the little fairy wagging her tush at a man holding a cigar. Was this intentional on the part of the filmmakers? Who knows? Sometimes a cigar really is just a cigar, after all.

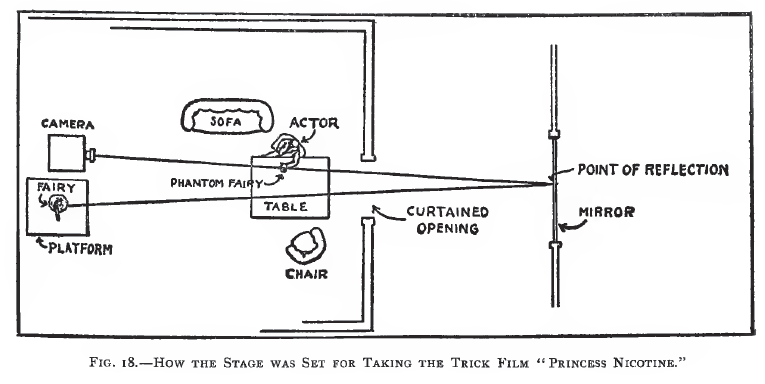

“Princess Nicotine” was produced and probably also directed by J. Stuart Blackton. Blackton was an British-American illustrator and early pioneer in trick cinematography, animation, live-action storytelling (frequently staged, often propagandistic) films. It was shot by visionary cinematographer Tony Gaudio, cleverly employing mirrors to display the tabletop action and a special camera lens to achieve the deep depth of field needed to keep both the reflected fairy and man in focus. Additionally, Blackton and Gaudio used stop-motion, hidden wires, double exposures, giant props and smoke to give the film a dream-like atmosphere.

The short movie was released by New York-based Vitagraph Company, which was at that time America’s leading film producer. Vitagraph had been founded in 1897 by Blackton and magician Albert E. Smith, focused on their mutual love of trick films inspired by the dreamy, fantastic films of Georges Méliès. While in the 1890’s and early 1900’s Thomas Edison threw his legal weight around enforcing patent infringement against independent studios that used his motion picture inventions, Vitagraph continued to operate under a specially-purchased license and shared distribution agreement from Edison in 1907. In 1909, in his attempt to corner the motion picture industry, Edison created the Motion Picture Patents Company (MPPC), a group of studios designed to operate as a cartel. Vitagraph was selected to be one of the ten companies that would be included in the MPPC.1 Edison’s group was disbanded in 1916 after losing its anti-trust suit of 1915. Vitagraph chugged along independently, albeit losing stature and business as the studio distribution system supplanted smaller studios, until 1925 when a majority of its shares were purchased by Warner Bros.

National Film Preservation Foundation: Princess Nicotine; or, The Smoke Fairy (1909)

Matt Malsky, Composer: Princess Nicotine (3/24/12)

Wikipedia: Princess Nicotine; or, The Smoke Fairy

IMDB: J. Stuart Blackton, Biography

Wikipedia: Motion Picture Patents Company

In response to pressure from MPPC, a majority of independent filmmakers moved their operations to Hollywood, out-of-reach from New Jersey, Edison’s home base. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, which covers this region in California, was loath to taking up patent enforcement claims. Additionally, Hollywood’s proximity to the Mexican boarder meant that pressured indy studios could take their equipment (and if necessary, their operations) out of the patent jurisdiction area if needed. Add the favorable weather and a countryside easily-adapted to wide variety of staging needs and Hollywood quickly grew in the first two decades of the 1900’s as THE destination for film studios. So now you know why so many American motion picture studios are based there.

I do love silent films. It is amazing the special effects they used that are still used today. For instance the forced perspectives they used in many scenes with the Hobbits and the bigger people in LOTR. A lot cheaper than CGI and still fools the eye. When you mentioned the MPPC my first thought was where's the anti trust people? And then there they were. Thanks Martini!

Did the filmmakers intend a double-entendre? As a fellow filmmaker, I must defend their honor, such as it is (selling out to Big Fairy, no doubt), a scene with more than one meaning- unthinkable!