Louis Wain

A troubled but visionary artist who foresaw our love of all things "cat"

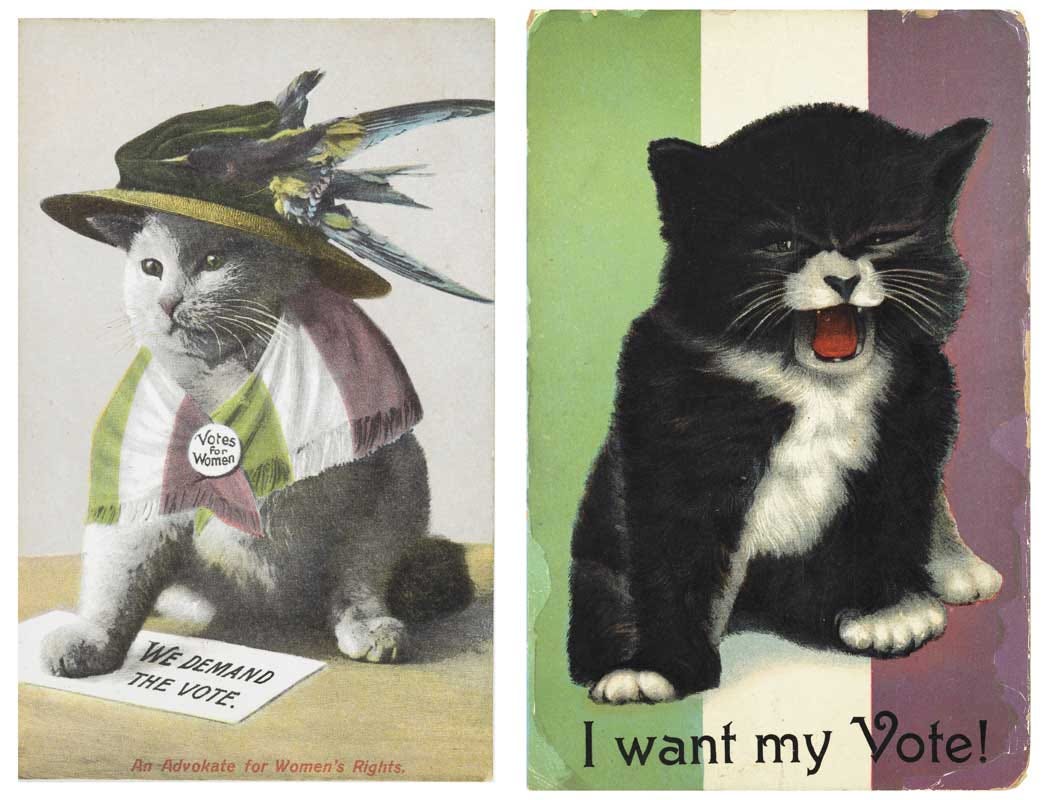

Cats; we love ‘em. The Internet is full of felines, with entire websites and memes and insta-channels devoted to their incredible physical abilities, adorable faces, quirky traits and personalities. As gratitude for paid subscription support,1 Rebecca is rewarding us this week with cat pictures on the pages of Wonkette. But our cat obsession wasn’t always this way. In the middle ages in Europe, for example, the cat was viewed with suspicion: a useful animal for controlling vermin, but not always trusted and frequently mistreated. The relationship between cat and man was complicated, certainly, even within the church—some traditions held that cats were linked to paganism and witchcraft, while at other times we find images of cats playfully depicted in manuscripts as friends and companions. Many Victorian-era homes kept cats as pets, even if they were not universally culturally beloved, and meat-sellers specializing in pet food would walk designated routes along the streets of London each day, with hungry cats mewling their arrival, expecting their dinner. On the other hand, cats were used as symbols by women’s suffragette opponents around the turn of the 20th century, claiming that allowing women to vote was no more useful than giving votes to cats.

While attitudes were slowly warming towards cats towards the end of the 19th century, one man in particular is credited with changing how we view our feline companions. That man is Louis Wain. His anthropomorphic cat illustrations were much loved throughout Edwardian society, making him a household name and elevating the cat’s reputation to cuddly household companion.

Born in Clerksenwell, England in 1860, Louis Wain was the eldest of six children and the only son. As such, it fell to him to care for his mother and sisters when his father passed. At first he supported the family with a teaching job at the West London School of Art, where he had been a student, but his talents led him to freelance work for trade journalists and newspapers. As printers lacked technology for reproducing photographs, they usually employed illustrators to create engravings—the speedy and adept Wain was well-suited to the profession.

When he was 23, Louis married his sisters’ governess, Emily Richardson and scandalized society and his family, both due to her position and because she was 10 years his senior. Sadly, Louis and Emily’s union was short-lived: soon after their marriage she was diagnosed with breast cancer. She only lived for three more years, Louis drawing caricatures of the family pet, a cat named Peter, as a way to cheer her during her declining health. While not originally intended as anything other than a private lark, the editors at one of Wain’s employers, the Illustrated London News, saw his drawings and offered to print some of his cat art. Only a few days before Richardson passed away, Wain’s A Kitten’s Christmas Party drawing was published in the newspaper. The drawing, containing images of cats doing human activities, was an instant success and catapulted Wain to stardom.

Louis would go on to create many more cat illustrations for periodicals and children’s books. In recognition of his expertise on cats, he was elected as president of England’s National Cat Club in 1890. His talents for cat drawings (and a myriad of other subjects) was in high demand, but he was not a shrewd businessman. The household expenses associated with caring for his sisters stressed his budget, and because he never copyrighted his work, his drawings were frequently reproduced without him gaining any financial remuneration. In 1914 he fell from the platform of an omnibus and suffered a head injury resulting in a coma, which left him hospitalized for three weeks. It was likely a combination of these financial stresses and injuries that led to his eventual admittance in 1924 into the pauper ward Springfield Mental Hospital of South London. While institutionalized, he continued to produce paintings that his sisters would then collect and sell.

Later friends in the publishing world, even involving writer H.G. Wells and the English Prime Minister, would hold fund raising events to improve Wain’s circumstances. He was transferred to more comfortable surroundings at the Bethlem Hospital and later to Napsburn Hospital in 1930. He continued to paint, with an exhibition of his work held at the Brooks Street Art Galleries in 1931, proceeds going to his surviving sisters. His later period work became more abstract and vibrant, but always exuberant despite any inner turmoil he might have suffered. Some speculate that his later works may have reflected Wain’s suffering from schizophrenia, but there is not universal agreement on that analysis. Many art watchers say Wain’s later pieces were important precursors to the psychedelic art movement that would happen a few decades later in the 1960’s.

Wain suffered a stroke in 1938 and in declining health passed away in 1939. A 2021 biographic featuring Benedict Cumerbatch, The Electrical Life of Louis Wain, is available streaming on Netflix.

More information about this fascinating artist can be found in the links below.

The National Archives, UK: Louis Wain

BBC: "Louis Wain: The artist who changed how we think about cats" by Tim Stokes, 12/28/21

Bethlem Museum of the Mind: Louis Wain (1860-1939)

Museum of London: "Cats in the collection: a feline history of London" by Alwyn Collinson, 7/31/17

We didn’t quite reach our goals this time, but Rebecca, the king of all of us, has deemed cat week a reality because she is wonderful and she loves us. Still, my dear friends, in this time where filthy, liberal, honest journalism is more important than ever, we would very much appreciate your patronage. Links to subscribe and support Wonkette are here for you:

Thanks very much!

Thank you Martini. These illustrations are wonderful. I'm glad Mr Wain changed people's minds. But what I don't understand is how, having met kittens, one could not also love cats. I mean, come on. A little ball of fluff with murder mittens - what's not to love?

Understandable- copyright laws started in the 19th century but didn't get real teeth, with the focus on granting the author direct control for their life plus x number of years after, until the 20th.