Gustaf Tenggren, Artistic Chameleon

While the 20th century illustrator isn't the household name he once was, you are almost certainly acquainted with his work

While looking through the images in today’s gif you would be forgiven if you thought that the different artistic styles therein must belong to different illustrators. But in fact, all these works are by the same man, Gustaf Tenggren. With a career spanning about 60 years through the early to mid-20th century, Tenggren lent his considerable talents to periodicals, advertisement campaigns, and to children’s books with styles he adapted to suit either younger or older readers, depending on the publication. One of his more notable contributions was as a storyboard illustrator and team manager for the animated full-feature films of the Walt Disney Company in the 1930’s—his influence is readily apparent in the animation masterpieces of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and Pinocchio.

Born in 1896, Gustaf grew up on a remote farm in the region of Väster Götland, Sweden. His father had abandoned his mother and family of seven children, leaving the boy to spend an impoverished childhood with his grandfather, a painter and woodcarver. Watching his grandfather work would have a profound influence on young Gustaf, exposing him to Scandinavian techniques and mythological subjects of Nordic folklore. When he was eleven years old, Gustaf was obliged to assist in the family finances and take work apprenticing in a lithograph shop. It was not long before his artistic talent was noticed and he was encouraged to attend art school, the local community raising funds to help pay for his initial tuition and expenses. A scholarship grant would further extend his scholastic endeavors into his later teens, even as he continued to work at the lithograph shop and on illustration and portrait commissions.

At the age of 20 Tenggren was hired as illustrator for the famous Swedish children’s Christmas annual, Bland Tomtar och Troll (Among Elves and Trolls). He was a natural fit for the position, his detailed line-art watercolors of fantasy subjects and style similar to the publication’s illustrator that proceeded him, Swedish artist John Bauer. It is probable that Bauer and Britain’s Arthur Rackham were influences during Tenggren’s study at school, both being well-known and popular illustrators of the day, particularly in the folkloric themes of trolls and elves that so attracted young Gustaf.

In 1920, looking for a wider and more lucrative audience, Tenggren and his first wife moved to the United States, settling first near the home of some of his sisters in Cleveland, OH and two years later relocating to New York city. Meanwhile he continued to support his family with commissions from European clients, primarily with book illustrations. Perhaps his most compelling work from this period was a series of illustrations done for a 1922 color edition of Grimms’ Fairy Tales, which showed a clear demonstration of his ability to bring written fantasy narratives to life through compelling visual imagery. However the book, lacking an American publisher, stayed largely unknown to the American marketplace for several years. Still, the move to the US paid off, and by 1924 Tenggren had a steady stream of projects from US clients, illustrating for books, magazines and in advertisement campaigns for large, established brand names such as International Silver Co and Elgin Watches. While his output in this part of his career largely relied on the Bauer- and Rackham-influenced style in which he excelled, he was remarkably versatile, incorporating stylistic elements from Art Nouveau, Cubism, Realism, and Expressionism as the assignment required.

In 1930, following his divorce from his first wife, Tenggren remarried. The two had moved from the city to a farm in upstate New York the prior year. While Gustaf, who had steadily developed into a recognized talent, was able to weather the Great Depression thanks to highly-sought quality work and a series of continuing commissions, the constraints on the publishing industry did impact his style. Where once expensive color illustrations filled a book or magazine, page illustrations of cash-strapped publishers would be commissioned as pen-and-ink monochromes, with perhaps a single color frontispiece or a small set of color plate illustrations. Still, Tenggren remained no less adept at bringing the written word to visual life; such as in the The Ring of the Nibelung (1932) by Gertrude Henderson with a triumphant Siegfried rendered for the frontispiece and compelling pen and ink images scattered throughout the book.

Walt Disney, in the meantime, had developed a taste for “old world” illustrators to help fuel the creativity in his budding animation studio and wanted to use this aesthetic in his first planned full-length feature movie, a retelling of the classic fairy tale “Snow White and the Seven Dwarves.” Having returned from a European vacation in the summer of 1935 and armed with a stash of picture books from England, France, Germany and Italy, he was reinvigorated with the realistic romanticism of the folklore illustrations within and had determined to further develop this style of fantasy art elements in his productions. Disney’s scouting team targeted Tenggren as an ideal candidate— an American-based artist with training and talent in European folkloric illustration—and by 1936 he had prevailed upon the illustrator to move to Hollywood. For a Depression-era artist, this full-time assignment (and the plum salary to go with it) was too enticing to pass up.

Engaged as Art Director for Snow White, Tenggren wasted no time putting his stamp on the Disney brand in his capacity of senior illustrator. The studio’s Oscar-winning Silly Symphony short The Old Mill owes an enormous debt to Tenggren’s artistic vision. He created dozens of continuity paintings showing the forces of nature and visualizations of animals, staged for maximum artistic impact, drama and beauty. Wide angles, close-ups and unusual perspectives were all exploited in Tenggren’s story-boarding. The film itself was a testing ground for a new animation technology that would be used in Snow White, the multiplane camera, designed to give an illusion of depth to 2D media. Disney studio departmental advances in special effects animation, layout, design and direction were all trial tested in The Old Mill in preparation for their eventual deployment in Snow White.

As a crafter for artistic direction, Tenggren was enormously successful at Disney. He was a meticulous researcher and kept clippings of contemporary painters, movie scenes with unusual angles and photos of reference locales. Images from his inspirational drawings—designed to be used as jumping-off ideas for the Disney team—found their way into several beloved animations, both shorts and full-length features. His visual approach to fearsome woodland fairy tale stories directly translated into the frightening woodland scenes of Snow White, wherein dark, gnarled anthropomorphic trees grasp sinisterly at the fleeing heroine, revisiting depictions he’d used in Bland Tomtar och Troll.

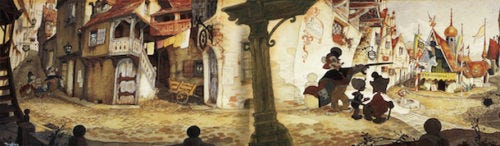

In addition to the woodland scenes, for other dramatic Snow White settings Tenggren relied on places from his childhood experiences, influences that can be found in the rustic cottage of the seven dwarfs and in the evil queen’s laboratory. His success on Snow White, led to other assignments, participating in scenes for such enduring favorites as Fantasia, The Ugly Duckling, and Little Hiawatha. He was particularly influential for Pinocchio, his practice of including Swedish and Germanic traditional dress translate directly into the Tyrolean clothing of the movie’s characters. The decorative woodwork and toys of Gepetto’s workshop recall those of Tenggren’s grandfather, and his sketches and studies of historic European towns, particularly of the medieval town of Rothenburg ob der Tauber in Bavaria, find their way into the movie’s street scenes and backgrounds. His interest in cinematic treatments can be seen in the scene where Pinocchio and the cat dance, viewed from a high, sharp perspective as well as in the “fish-eye” renderings given to several ground-level street scenes.

As a studio team-mate, however, Tenggren was neither successful nor particularly interested in collaboration. It might have been due to his Swedish cultural approach social distance, or perhaps because Tenggren already fancied himself an illustrating superstar above the fray, but regardless, he primarily kept to himself. Many of the Disney animators found his aloofness off-putting and snobbish. Tenggren had, by most accounts, a problem with alcoholism, which would on occasion impact his work life. And his reputation for womanizing didn’t help matters either, particularly after he became embroiled in a scandal involving an intern, the underage niece of another top animator.

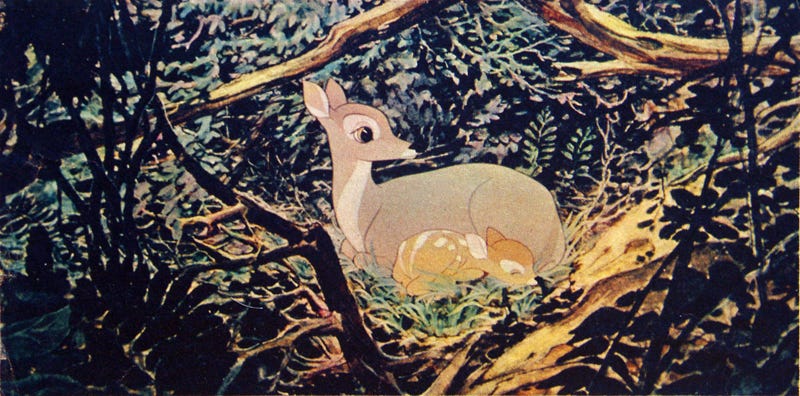

After three years at Disney, Tenggren departed due to the sufficiently vague reason of “artistic differences.” He may have felt that his studio contributions were not sufficiently credited: long after his separation from Disney, he would tell a niece that it was better to burn a piece of art than to give it away, alluding to is tenure at Disney. He may also have been dissatisfied with what he believed was a low salary from the studio, considering what he believed to be his demonstrated star power. Certainly, the workplace friction with other animators hardly helped the matter. Whatever the reasons for his exit, Tenggren was vocally frustrated with what he believed to be the studio’s prioritization of speed over artistic merit. His woodland sketches for Bambi irked the animation management, each painting taking over three days to complete. Fearing that the movie would never get made if it were animated in such painstaking detail, the studio determined to go in a different direction, using a more minimally detailed impressionistic style. In any event, there were some hard feelings on both sides: when Disney finally released Pinocchio in 1940, a year after Tenggren’s departure, his name was nowhere to be found on the credits of the movie he’d contributed so much to.

In 1940, having resolved to never again waste his skills on building a reputation for someone else, Tenggren produced his first in a series of children’s books branded with his own name, The Tenggren Mother Goose. This followed with others: The Tenggren Tell-It-Again Book, Tenggren’s Storybook, Tengtgren’s Farm Stories, Tenggren’s Folk Tales and Tenggren’s Pirates, Ships and Sailors. Interestingly, while he certainly had made his mark on the Disney brand, his work post-Disney show that the studio had, in turn, influenced his way of working. The style in these new books changed from complex line drawings and color-and-shade work to simpler and faster-to-paint flat blocks of colorwork with minimal shading, albeit charming in their own way. From 1942 to 1962, Tenggren was engaged by Little Golden Books as an illustrator of books for younger audiences. Of those, The Poky Little Puppy (1942) became the best-selling hardcover children’s book written in English, selling over 15 million copies.

The 28 books he illustrated for Little Golden Books developed their own particular illustrative format, one that became in their own way a demonstration of American mid-century style. The classic Golden Book style showcases a streamlined and simplified character design, with a clear, simple and balanced presentation. As his method evolved, his illustrations focused largely on character drawing: he removed background elements or included islands of color rather than plates that took up the entire page, with the illustrations meant to float alongside blocks of text. As ever, his innate sense of adapting the narrative to a visual element dominated his work, but this time it was pared ever finer to the most basic but essential elements of storytelling.

While he would never again illustrate in the highly-detailed pen and watercolor Rackham/Bauer way in which he started his career, the ever-adaptable Tenggren would again revisit the artistic themes he used in some of the more detailed drawings reminiscent of his earlier years. The output largely depended on the audience, with books for older children commanding more ornate design. But one thing that appears in these later works is a motif of phallicism. In at least a dozen of his illustrative book paintings, Tenggren overlays the crotches of his male characters with strategically placed knives, poles, or guns. In perhaps the most blatant example, found in Tenggren’s Story Book (1944), his Robin Hood character approaches a shyly smiling Maid Marian with a large plucked goose, it's neck and head extending between his legs to the ground, the caption reading “Now come, ye lasses, and eke, ye dames, And buy your meat from me.” It’s hard to know if the phallic symbolism was intentional or unconscious or Tenggren’s part, perhaps a winking joke lobbed at the banality of children’s book illustration, or perhaps a subconscious and/or questionable decision making laid bare by alcoholism.

In 1945, the Tenggren’s moved to Dogfish Head, Maine, settling in a large, old house that they furnished with Swedish folk antiques. Gustaf loved the house and its surroundings, with the firs and pines reminiscent of the Sweden of his childhood. In his later years, he became even more introverted and stern, depression overwheliming him at times due to declining health. During the 1960’s he focused on a series of highly pessimistic paintings inspired by Silent Spring, Rachel Carson’s book about enviornmental waste and devistation.

He continued illustrating children’s books and exhibiting paintings until his death of lung cancer in 1970. Although he’d become fully an American icon of illustration and a major contributor to the asthetic of America’s golden age of animation, he carried a fondness for his Sweedish heritage througout his life; an immigrant incorporating his own rich culture into the melting pot of America. His wife donated many of his non-Disney illustrations to the University of Minnesota and are now part of the Kerlan Collection, a special library focused on children’s litterature.

A thorough study of Tenggren’s artistic evolution with examples and an analysis of the drawing techniques used is shown in the embedded video. It’s well put together and worth of watch.

To learn more about Tenggren, here are some links to get you started:

Illustrators' Lounge: "Gustaf Tenggren (1896–1970)" by Mr. Geo Neo, 12/9/15

CanalBlog: The Art of Disney > Gustaf Tenggren (in French), by Cobain59, 8/2/07

A big thank you to reader Craig Nixon for providing editing assistance on this post!

Yes, Thank you! What a feast you have given us today!

Well this one made me very nostalgic. Made me think of my late maternal grandfather, the only one of my grandparents I had a connection with. Being shy I did not like being questioned by people and my other relatives were always trying to talk to me. Grandpa did not so I spent as much time as I could with him. He made his living painting houses and carpentry work but his hobby was painting pictures. When I was 10 grandpa set out to do a painting for each of his 36 grandchildren. He asked each child what they wanted. Being a typical little girl I wanted horses. My house has a dozen paintings by him starting with one he did when he was 12. And you mentioned The Old Mill and my feelings came flooding back. The fear for all the little animals in the storm but especially the bird on her nest. Thank goodness that cog was missing from the wheel. I mean the bird could leave the nest but what about her precious eggs? And the Poky Little Puppy, of course we had a copy of that, didn't everybody? Whew. My brain is going to be thinking about this stuff all day. Thanks, Martini!