Alla Nazimova's Salomé

An artist’s ambitious attempt to elevate the medium of motion pictures

Today’s gif shows a segment of the Dance of the Seven Veils from 1922’s Salomé, a highly-stylized silent movie that some describe as the first art film to be made in the United States. The drama, starring Alla Nazimova as the titular figure, was also conceived, produced and primarily funded by the Russian-American actress. The film is based on the play of the same name by Oscar Wilde and takes its cues for costuming and set design from the Aubrey Beardsley illustrations in the printed version of Wilde’s play. Nazimova’s artistic collaborator—colleague, friend and possibly also her romantic partner, Natacha Rambova (who, a year after the movie’s release, would marry actor Rudolph Valentino)—designed the lavish and expensive costumes, created exclusively by Maison Lewis of Paris. Nazimova’s husband Charles Bryant is credited as director, although it is clear that Nazimova’s vision was the one that governed the movie’s action and artistic choices.

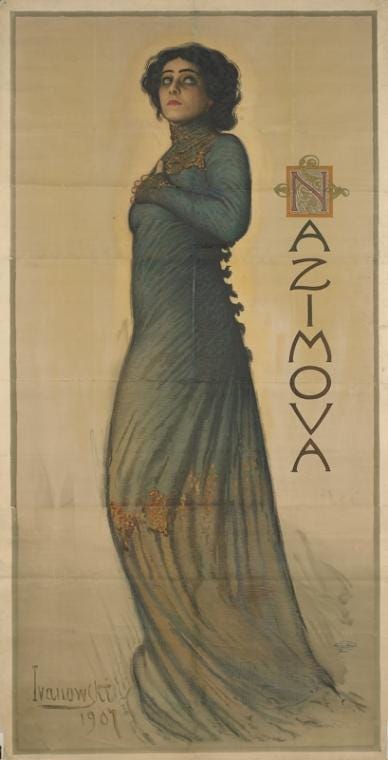

Born on or around 1879 in Yalta in the Crimera (then Russia, now part of Ukraine), Marem-Ides Leventon (in Russian “Adelaida Yakovlevna Leventon”) was the youngest of three children in a turbulent family with a father who was physically abusive and controlling. She showed a talent for acting early, sneaking into her father’s pharmacy after hours and performing impersonations of her father and his customers for the employees. She studied violin at her father’s insistence, and was skilled enough that she might have had a future in music were it not for the lure of the stage that finally took her imagination. A series of her mother’s marital indiscretions precipitated in her parents divorcing when she was eight and led to an unsettled and rebellious childhood, Alla living in turn with relatives, in foster homes, with her remarried father, or at boarding school. As a teenager she boarded with a woman whose daughters were actors, and Alla soon was excitedly joining them in studying roles, analyzing plots, aiding in rehearsals, and assisting at their theater with costuming and backstage support. When she was 17, her brother, under whose guardianship she’d been assigned due to her father’s illness, finally permitted her to study acting. After study at the Academy of Acting in Moscow, she joined the Moscow Art Theater, taking the stage name of Alla Nazimova: the surname comes from Nadezhda Nazimova, the heroine of the Russian novel Children of the Streets. The theater company, founded by Konstatin Stanislavsky and Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko, was conceived as a venue focused on organic, naturalistic acting (this would later evolve into the concept of “method acting”) and would become highly influential in the development of modern film and stage acting.

Splitting her time between the Moscow Art Theater and regional companies, Nazimova married fellow acting student Sergei Golovin in 1899. This was primarily a marriage in name only, as Alla wasn’t sticking around for long. Disillusioned with the controlling and increasingly conservative Stanislavsky, she departed the Moscow company and joined the Kostroma stock company where she met the flamboyant Pavel Orlenev, an established actor and producer, and close friend of well-regarded playwrights Anton Chekhov and Maxim Gorkey. Orlenev and Nazimova began a relationship based both their attraction for each other as well as their great passion for Russian theater. In 1904, their company received permission to tour Europe and in 1905 they were invited to New York, where they established a Russian-language theater on the Lower East Side, performing the works of Chekhov and Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen. While the theater venture proved unsuccessful, Nazimova’s performances thrilled audiences and attracted attention. Although the theater folded and Orlenev and company were obliged to return to Russia, Nazimova stayed the US, having signed with American theater producer Lee Schubert with the stipulation that she learn English, which she did in less than six months. Her Broadway debut in 1906 in the role of Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler was a popular and critical success.

In the decade that followed, Alla Nazimova developed into a legendary theatrical talent. She would alternate her time between “serious” plays by Ibsen or Chekhov and more lighthearted affairs. She was so popular that when the Shubert family theater on 39th and Broadway was opened, they named it “Nazimova’s 39th Street Theater.” Or at least it was so-named until the two dissolved their business partnership: despite Shubert’s offer of financial incentives and profit sharing, Nazimova signed with the Charles Frohman production agency in 1911. While appearing in a play for her new producer, she met Charles Bryant, the man who would become, at least in the public eye, her husband. Because she had not divorced from Golovin, the marriage to Bryant was never legally registered. Further, by this point in her life, the bisexual Nazimova had started to prefer lesbian relationships. Regardless, Bryant and Nazimova would claim to be married for the next 15 years, an arrangement that benefited them both; the reputation and career that might otherwise have suffered from Nazimova’s sapphic dalliances would be given cover under a “lavender marriage,” while Bryant could grow his own fame following in the footsteps of his more established wife. Regardless, the free-spirited Nazimova would continue to have affairs with both men and women throughout her life, frustrating Bryant to the point of leaving her for good in 1923 and marrying another woman in 1925. Thus the press learned that Bryant and Nazimova’s marriage had been a sham, and her reputation suffered for the deception.

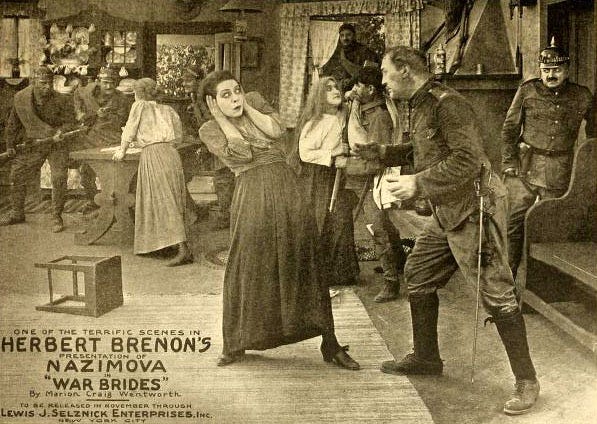

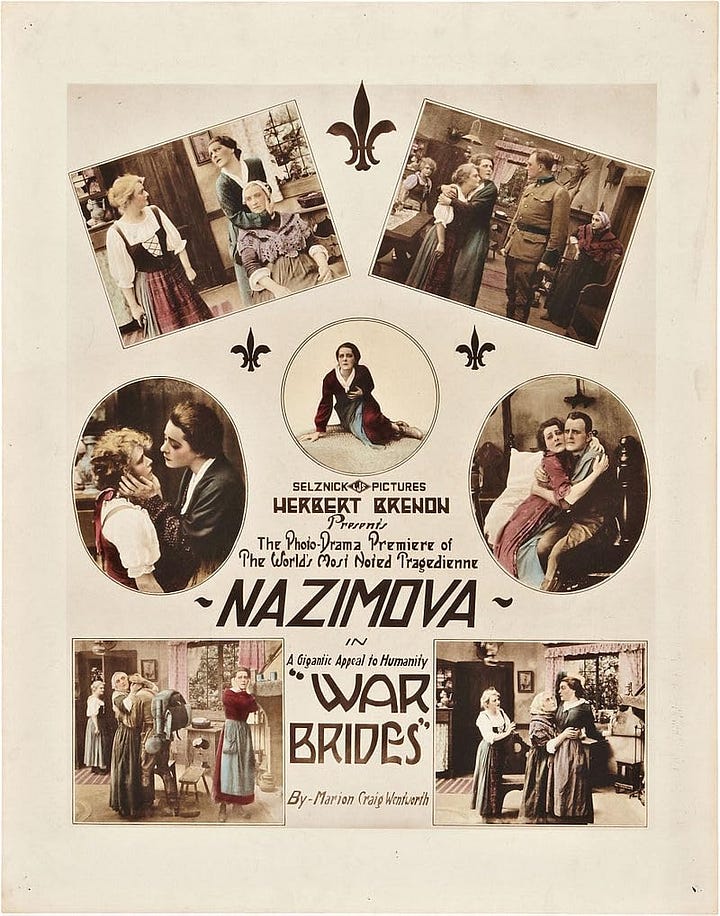

Alla Nazimova’s first film role came in 1915. With the outbreak of World War I, she had been offered the lead role of Joan for the pacifistic-themed War Brides, a theatrical play written by suffragist Marion Craig Wentworth. The stage production captured the attention of Lewis J. Selznick (also born in the Ukraine and whose son David O. Selznick would become a famous Hollywood filmmaker). Selznick asked Nazimova to reprise the stridently-feminist role of Joan for a silent film adaptation of the play. Nazimova accepted and starred, earning $30,000—that’s over $930,000 inflation-adjusted for 2024—with a bonus of $1000 for every day the shooting went over schedule. Sadly, the film has been lost to time, but publicity remains.

With the success of War Brides, Nazimova’s stage celebrity morphed into screen stardom. In 1917 she was given a 5-year contract at Metro Pictures Corporation with a salary of $13,000 per week, becoming the highest-paid female film talent, earning $3000 more per week than even the superstar Mary Pickford. Nazimova learned early to exert control over her career and her image, and her relationship with the studio reflects the power that she wielded. Her new contract gave her approval rights for director, script and leading man. Starring opposite Bryant, her next two movies, both melodramas, were financial and audience success. After taking a break from cinema to focus on some theatrical work on New York stages, she was persuaded to move to Hollywood. In total Nazimova appeared in 17 motion pictures, from potboilers to silent-screen versions of her stage successes.

In 1918, with her film career flourishing and the impressive earnings to match, Nazimova bought an imposing California Spanish home on Sunset Boulevard (at that time, still an undeveloped dirt road), naming it The Garden of Alla. The house would become renowned as a place where the local intelligentsia would gather for art salons, deep discussions of plays and other artistic endeavors much like those gab sessions with her boarding housemates that so excited her when she was young. In addition to the intellectual gatherings, she would also host lavish, debauched parties—anyone who was anyone in Hollywood wanted to attend these shindigs, Nazimova skillfully managing the guest lists. Later, after she developed the property into a hotel to stave off bankruptcy, finally selling it, the site became a hot spot for Hollywood elite and famous to stay. Throughout, The Garden of Alla was acknowledged by those in the know as a notorious gathering spot for the most famous lesbians of Hollywood. Nazimova is credited for creating the term “sewing circle,” a winking inside joke, code for non-heterosexual actresses of the day that hid their true sexual identity.

During her contract with Metro, Alla created Nazimova Productions, active from 1917 to 1921. In addition to acting, she filled many of the roles in film production: directing, editing, lighting designer, and even costume design. Under her pseudonym Peter M. Winters, she wrote screenplays. While her early works were financial and critical successes, by the 1920’s her popularity had waned. As her celebrity began to falter, Nazimova began to take greater aesthetic risks. Along with her more avant-garde artistic approach, she also hoped to explore a stronger gay sensibility in her productions. But fearful of poor audience reception, government censorship interference and studio financial losses, Metro executives cancelled Nazimova’s audacious lust-and-violence packed production of Aphrodite. Instead, they green-lit approval of a futuristic Art Deco production of Camille (1921), with Nazimova playing opposite Rudolph Valentino.

Valentino, who would develop into the era’s biggest cinematic sex symbol, was recently divorced. His brief first marriage to starlet Jean Acker had ended after it was revealed she was involved in a love triangle with fellow actresses Grace Diamond and none other than Alla Nazimova herself. Still, it was hard to avoid Nazimova’s orbit, such were her connections and pull in the industry. And it’s possible that Valentino’s union with Acker had also been a “lavender marriage”—it would have been box office suicide if the actor that made the ladies swoon was revealed to be a homosexual (although biographers differ on opinions as to whether the star was straight, so his sexual orientation remains unclear). In any event, he could hardly have held too much of a grudge, agreeing to appear opposite as Nazimova’s romantic opposite in the silent film drama.

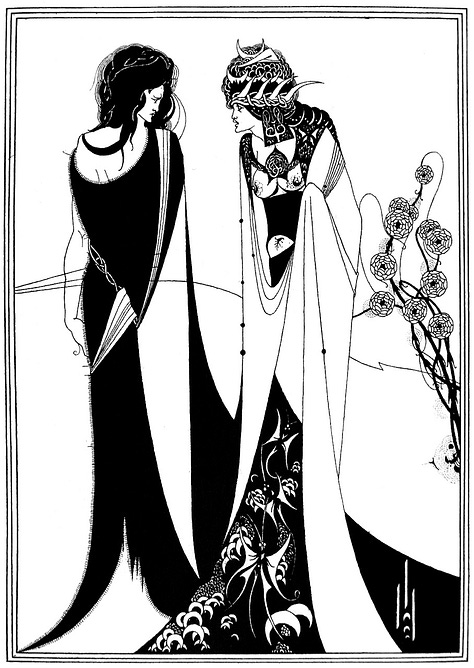

In choosing the “look” for Camille, Nazimova called on her friend and artistic collaborator Natacha Rambova. The two had met and become fast friends during the filming of the comedy movie Billions. Nazimova was impressed with the costumer designer’s artistic vision and interpretive skills, enough that she requested Rambova’s assistance for her precious but ultimately doomed Aphrodite vehicle. Therefore, Nazimova was pleased to ask her friend to act as art director for Camille. Always the Hollywood social facilitator, Nazimova introduced Rambova and Valentino, a successful pairing: the two were tying the knot of matrimony the following year. For the film, Rambova designed a series of outfits and settings based on the Japonisme of Art Deco, influenced by the drawings of enfant terrible English illustrator Aubrey Beardsley.

Camille concluded Nazimova’s time with Metro. She was no longer the box office draw that guaranteed the big receipts that might have otherwise offset the challenges of managing a demanding star. And for her part, Nazimova had tired of the femme fatale roles she felt she was often slotted into and decried the Hollywood scenarios on offer as “kindergartenish.” She wanted absolute artistic control and was determined to chart her own path for her next venture. I imagine that at this critical juncture in her career, she took a good, long look at her acting trajectory and longed for those meaty, weighty theatrical roles by literary master playwrights on which she had built her Broadway career and for which she had received such acclaim.

In this light, the choice of Oscar Wilde’s play Salomé makes sense. Wilde had originally written the play, a more sexually-charged retelling of the biblical story of King Herod and his stepdaughter, for the leading French actress Sarah Bernhardt, a theater actress frequently lavished with the same acclaim as Nazimova. Bernhardt never performed it, however, as she was engaged to work in London at the time and, at least as the official explanation went, censorship rules prohibited Biblical stories from being staged. The story itself was probably more racy than many fin de siècle theaters were willing to host: Herod is presented as lusting after Salomé, the daughter of his new wife Herodias; meanwhile Salomé’s young libido is aroused by John the Baptist (named “Jokanaan” in Wilde’s version), imprisoned for insulting Herodias, and meanwhile a member of the court has his own head turned by the pretty young lady. Salomé, stung by Jokanaan‘s rejection, plots revenge upon his head, bending Herod to her will by performing a highly seductive dance, “The Dance of the Seven Veils,” a concept that Wilde created for the play. Steamy! But also quite poetic, at least according to critics of the time who praised Wilde’s prose, written in French—although some called Herod’s speeches overlong. Any attempts to translate the play into English were deemed failures.

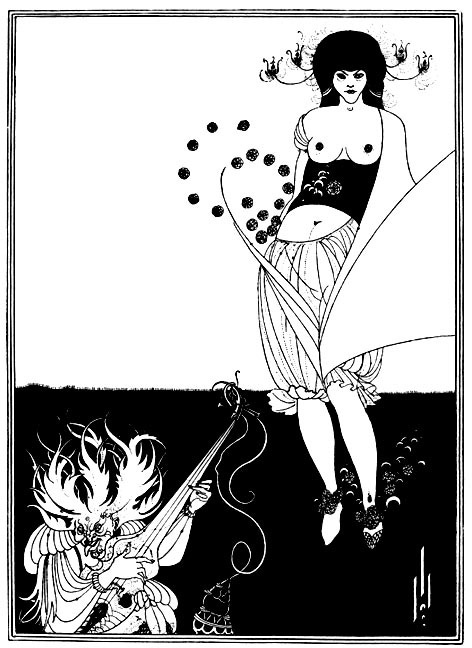

Accompanying the printed version of Wilde’s play were provocative illustrations by Aubrey Beardsley. Beardsley was perhaps the most controversial artist of the Art Nouveau era, known for his dark and perverse images, grotesque erotica and his skewering of Victorian high society. His style was heavily influenced by Japanese woodcuts, the flowing lines and heavy black and white contrasts. Rambova and Nazimova had used Beardsley as an inspiration jumping off point for their previous collaborations, so naturally Beardsley’s Salomé images would feature heavily in Nazimova’s screen adaptation of the play. To these visionary collaborators, historical accuracy was far less important than the elevation of film as an art, one that would unify design, staging and gesture at the highest level that the medium of movie cinematography could offer. They revamped the play, whittling down Wilde’s flowery language and Herod’s long-winded speeches into a short series of intertiles, choosing to let visual elements tell the story.

With Nazimova’s desire to incorporate more gay subtext into her productions, the Wilde-Beardsley connection likely was an important consideration in choosing the play. Wilde had been jailed for two years for homosexuality, and Beardsley (who died quite young and probably as a virgin) was hounded as a homosexual due to his association with Wilde, losing his publishing job following his collaboration with Wilde on Salomé. Additionally, it is rumored that Nazimova heavily recruited from the gay and lesbian community for her Salomé movie. Some accounts have the cast and crew being almost entirely homosexual, although this is probably unlikely. But certainly, in her version of the story she included a subplot relationship between courtesans as ambiguously gay, and some roles are played by actors in drag.

Thanks to a foundation undergarment specially designed by a tire company, the 43-year-old actress is almost believable as a girl of 14. But most critics of the era ridiculed what was to be a seductive dance as anything but. Still, it’s very unlikely that even in pre-code Hollywood Nazimova would have been able to dress much more scantily than the micro-mini that Rambova had designed for her. While the interior stage settings were kept minimal to most effectively control lighting design for cinematic effect, the imported French couture costumes were costly—Rambova designed lavish Beardsley-inspired robes and extravagantly theatrical accessories, and she insisted on real silver lame for cast loincloths in order to give beautiful shimmering effects for the camera. Perhaps the most memorable costume element is the bobble headdress that Nazimova wears in the early part of the movie, which was designed with real fresh water pearls (this headdress was recently rediscovered—see the linked article below).

Just as Salomé’s headstrong desire to assert her will mirrors Nazimova’s own drive to see her artistic vision fulfilled, so does her downfall follow a similar trajectory to that of her creator. At the completion of her dance, the girl requests the head of the captive and captivating Jokanaan to be served to her on a platter. As it is delivered, she bends down to kiss the lips of the man that would not have her while alive. Herod is so aghast at Salome’s bloodthirsty request—and perhaps additionally stung by rejection, her favoring a severed head to his own—that he orders her killed.

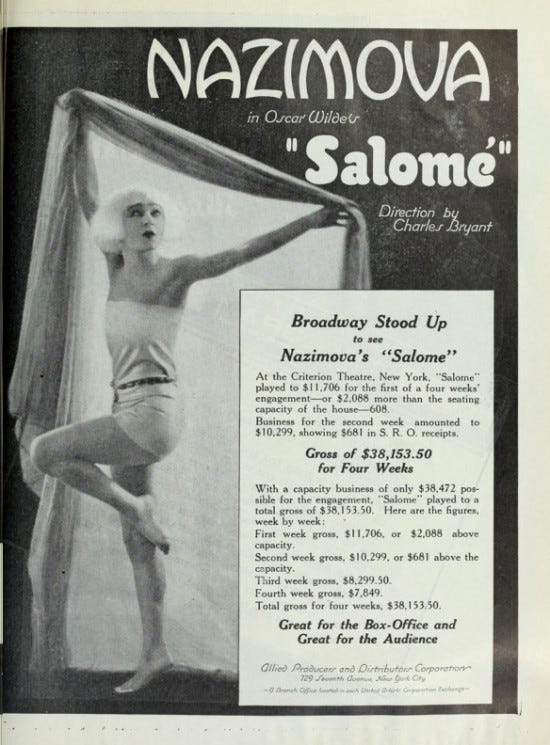

Sadly, the movie was a financial flop. Already well over-budget in production, Nazimova had unwisely spent even more of her own money booking a four-week exclusive theater venue in New York for the screening of Salomé. She spent more on publicity and advertising in one week than the film’s total revenues. Universal Studios agreed to distribute the movie, but it did no better in general release. Nazimova Productions folded soon after, the actress returning to the theater stage to support herself. Although she did appear in a few movies towards the end of her career, she was never again the high-flying darling of Hollywood cinema. But even though her star had diminished, she was still a social engineer with connections. In 1921, her friend from stage acting, Edith Luckett, gave birth to a daughter Nancy and asked Nazimova to be godmother—this child would grow up to be the future Nancy Reagan.

Nazimova moved back to Hollywood in 1938, renting a villa at the renamed Garden of Allah Hotel, where she lived with her longtime girlfriend Glesca Marshall until her death due to coronary thrombosis in 1945. Her contributions to the film industry have been recognized with a star on Hollywood’s Walk of Fame.

You can stream the movie from the Internet Archive by clicking here.

San Francisco Silent Film Festival: "Salomé" by Catherine A Surowiec, 2022

Library of Congress Film Preservation Board: "Salomé" by Martin Turnbull

Movie Jawn: "Nazimova and Salomé" by Ryan Smillie, 4/5/2018

Women Film Pioneers Project: "Alla Nazimova" by Jennifer Horne

New York Times: “A New Salome”, staff writer, 1/1/1923

Wikipedia: Salmoe (daughter of Herodias)

Messy Nessy: “Behind the Photograph: A Tale of Two Hollywood Lovers” by Zakiyyah Job, 8/5/2021

ABSOLUTELY GORGEOUS! The most delicious design, crystal clear storytelling. This my first real exposure to Nazimova. Awesome!

The TABS lettering tickled me. Thanks MG!

Ta, Martini. What a herstory!